Our van stopped at a scenic vista on the contour road where verdant mountains undulated southward toward China’s border with Laos. Stepping out to take some photos, I was overcome by an acrid, unpleasant odor. I asked my local travel partner, Xiao Guan, what the stink was.

“Money,” he said with a wry smile. “That’s the smell of money, my friend.”

He pointed to a small rubber plantation where latex was being processed. After I took some photos and boarded the van, I noticed rubber plantations everywhere we went.

It was late 2010, and I was traveling through the countryside in the Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture, a tropical area roughly the size of New Jersey in Southwest China’s Yunnan province, primarily populated by the Dai ethnic group. In addition to being home to eight of China’s minority ethnic groups, Xishuangbanna is known for pu’er tea, wild elephants, and the Lancang River, which flows out of the region as the Mekong to form the border between Laos and Myanmar. According to a recently released report, land under rubber cultivation in Xishuangbanna nearly tripled between 2002 and 2010 to account for more than a fifth of the area’s total land. On each of my several visits to Xishuangbanna since 2010, rubber’s positive impact on local livelihoods, especially among ethnic minorities, has become increasingly pronounced, with traditional wooden homes giving way to modern concrete and rebar edifices and cars replacing motorcycles. But recent research by Chinese and Western ecologists suggests the industry could collapse in the near future if new management strategies are not applied.

Rubber’s improvement of the fortunes of this former economic backwater was evident to me most recently when I attended the wedding of my friends Eddy and Tingting in February of this year. The newly married couple lives in Yunnan’s capital, Kunming, where Eddy, an Italian, works as a consultant and Tingting, an ethnic Hani originally from Xishuangbanna, manages a restaurant.

The final stretch of the ten-hour bus ride from Kunming followed a small country road lined with rubber plantations extending up and over mountains in both directions, until at last we arrived at Tingting’s home, a small rural cooperative growing—you guessed it—rubber.

The next day, 800 people attended the wedding banquet, including Tingting’s local friends and family, the couple’s friends from Kunming and other Chinese cities, plus Eddy’s friends and family from Italy. Most of the locals I spoke with said they had invested in the new rubber economy. Eddy even received a small plot of rubber trees as part of Tingting’s dowry.

Looking up from the basketball court where happy diners washed down an opulent feast of plate after plate of spicy Hani- and Dai-style meat and fish dishes with beer, Chinese grain alcohol called baijiu, and Italian wine, I couldn’t help but feel that the rubber trees towering above us on the surrounding hillsides were the dinner’s silent VIP guests.

The previous night, in the nearby town of Damenglong, two men of the Akha ethnic group invited me for a drink. When I asked them what they did for a living, they told me they had low-paying day jobs in local companies, which they supplemented with income from their rubber tree holdings. One of the men boasted to me that he was making six figures in U.S. dollars every year from his rubber holdings. How were the people in this remote corner of one of China’s poorest provinces making so much money off of rubber? The answer was right outside in the parking lot filled with the wedding guests’ cars, all made in China by domestic and international manufacturers.

In 2009, China overtook the United States as the world’s largest market for new automobiles. The China Association of Automobile Manufacturers predicts seven percent growth in 2013, fuelled by continued economic growth and growing demand for Chinese cars overseas. In 2010, there was roughly one automobile for every 17.2 Chinese, compared with one for every 1.3 Americans. Today, China is the world’s largest manufacturer of automobiles.

China’s car boom has not only created extensive auto-focused supply chains on the banks of the Yangtze and Pearl rivers, it also has changed the fortunes of farmers in Xishuangbanna. Cars need tires, and this mountainous, lush pocket of southwestern tropical China is a crucial producer of natural rubber for China’s massive tire market, which constitutes about one-quarter of global tire demand.

Around forty-two percent of the rubber consumed worldwide in 2013 will come from rubber trees, while the rest, according to Singapore-based International Rubber Study Group, will be synthetic rubber made from petroleum.

Natural rubber is derived from latex, a viscous substance produced beneath the bark of the tree Hevea Brasiliensis, which, after being treated with acid and rolled out, can be used to make a wide range of consumer goods.

Rubber trees must grow for about seven years before they can produce latex. Once mature, a tree can be tapped once a day, every two or three days, for around twenty-five years.

Today, it is difficult to travel in Xishuangbanna without encountering rubber plantations. Mountains covered by nothing but rubber trees are a common sight throughout the area. This is not Xishuangbanna’s first experience with cash crops, but it is the first time that so much of its land has been converted to grow just one species.

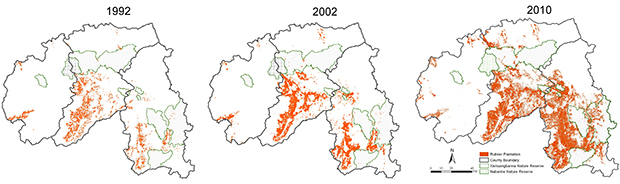

Rubber Plantation Coverage

Monoculture rubber plantation coverage in Xishuangbanna, seen in orange; and nature reserves, outlined in green.

Map Credit: Xu Jianchu, R. Edward Grumbine, and Philip Beckschaefer

Xishuangbanna is home to some of China’s most renowned tea mountains. The ethnic Bulang, who traditionally managed the tea trees of Xishuangbanna’s mountains, integrated tea planting with forest ecosystems using principles of what is known as agroforestry. This approach facilitated tea cultivation with minimal impact on the region’s ecosystem and biodiversity.

Although portions of many mountains in the area were clear-cut to maximize tea production, many locals claim the best tea comes from the oldest plants, some of which, they say, are more than 1,000 years old. One of the more famous mountains, Nannuo Shan, is dotted with such tea trees, scattered throughout a sea of plant diversity. Many of these trees supplied the ancient Tea Horse Road network of trade routes that for centuries connected Xishuangbanna with thirsty tea drinkers in China, Tibet, and beyond.

Xishuangbanna covers only 0.2 percent of China’s land area, yet it contains sixteen percent of the country’s vascular plant species, and is home to more than one-fifth of its mammals and well over a third of its birds—a spectacular biodiversity now threatened by rubber’s spread. In domestic terms, the prefecture’s rubber output is second only to that of Hainan, an island province in the South China Sea.

Native to Brazil, the rubber tree has grown in Xishuangbanna for more than seventy years. In 1940, government researchers planted the first rubber trees in the area. These initial plantings were followed in the mid-1950s by the first state-run plantations. Under the land reforms of the 1980s, the local government allocated plots to farmers for the first time since collectivization.

Since rubber tapping isn’t particularly labor intensive and yet yields a high-return, many farmers enticed by growing demand have felt justified creating slash-and-burn farms consisting solely of rubber trees. Monoculture plantations maximize rubber tree coverage, but they are green deserts; compared with natural forests, massive stands of rubber trees do little to sustain other plant or animal life, according to R. Edward Grumbine of Prescott College in Arizona, who, as a senior scholar with the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), has researched recent land-use shifts in Xishuangbanna.

According to data from the U.N. Conference on Trade and Development, annual average free market prices for blocks of benchmark TSR20 rubber (the light sweet crude of the latex trade) rose to nearly $5,000 in 2011, up from $1,000 per metric ton in 2003. “Rubber cultivation has made ethnic minority farmers really rich in the context of China,” says Janet C. Sturgeon, Associate Professor of Geography at Simon Fraser University in Canada. Sturgeon has been studying rubber’s impact on the ethnic minorities of Xishuangbanna since 2002.

“Rubber farmers I interviewed across Mengla county [one of Xishuangbanna’s three counties] averaged about $30,000 in annual household income,” she said. “I was totally astonished. Rubber farmers had better incomes than workers on state rubber farms.” Annual income at this level would put a family firmly in the middle class in China’s more prosperous coastal cities, but in Yunnan, one of the country’s poorest regions, it affords a very high standard of living.

Xishuangbanna’s rubber boom is driving monoculture rubber plantations into areas previously considered too steep or too high for planting rubber trees. Plantations also are encroaching on protected areas and many local rubber farmers are expanding their holdings over the border into Myanmar or Laos and importing half-processed rubber back to Xishuangbanna.

In a recently released report, Grumbine and his CAS colleagues Xu Jianchu, and Philip Beckschaefer examine the spread of monoculture rubber plantations throughout Xishuangbanna from 1992 through 2010. Working at the Kunming Institute of Botany’s Centre for Mountain Ecosystem Studies, the team used satellite imagery to track changes in land use. It found that Xishuangbanna’s rubber plantation coverage had exploded over the eighteen-year period. In the ten years from 1992 through 2002, the total area covered by rubber farms in Xishuangbanna jumped seventy-seven percent, to 154,000 hectares, up from 87,000 hectares. In the following eight years, up to 2010, rubber coverage jumped 177 percent to 424,000 hectares.

By 2010, more than twenty-two percent of Xishuangbanna’s land was growing rubber, a calculation that doesn’t account for the crop’s intrusion into the Xishuangbanna and Nanbanhe Nature Reserves, which Grumbine describes as “significant.” Grumbine, Xu, and Beckschaefer’s findings show that Xishuangbanna’s rubber industry at present is anything but sustainable.

Rubber plantations sequester less carbon than natural forests and their spread has led to a substantial net release of carbon dioxide. Because after the first few years the plantations require chemical fertilizers that often contaminate nearby bodies of water, oxygen-sapping algae can bloom and kill off fish and other aquatic species.

In addition, since rubber trees use more water than native vegetation or other crops, especially during the typically hot months from November through April, the area’s dry season is growing longer. According to the trio’s report, both the number of foggy days and the amount of fog on those days is declining, affecting other agricultural production and regional food security.

The team’s paper concludes that if the local climate continues its hotter-and-drier trend, it could become unsuitable for growing rubber altogether, a development that would devastate the local economy.

Rubber is drastically altering Xishuangbanna’s landscape. For residents of an inland area largely left behind as much of coastal China got rich as the result of the reform and opening-up policies of late 1970s, the change to the land is a sacrifice many have been willing to make.

Small-hold rubber farms now cover more of Xishuangbanna than do state farms. In addition to being less productive than state farms, small-hold farms often use land that is not suitable for rubber trees. Local officials have encouraged small farmers to convert their plantations back to natural forest, but local government also benefits from increases in regional GDP and has provided few economic incentives for farmers to change course. In the meantime, rubber farmers continue to tap their trees and make money.

“Rubber farmers are now able to build huge new houses, buy the latest model cars, get bank loans for new businesses, and send their children through school, including university for those who qualify,” Sturgeon said. “They see themselves as successful entrepreneurs in China’s booming economy.”

Yi Zhuangfang, a daughter of small-hold rubber farmers, not only went to university and became the first Dai woman to earn a Ph.D. in Xishuangbanna, but wrote her doctoral thesis on how to create a more environmentally friendly rubber industry.

Yi said her research bridged a gap between her parents, who depend on rubber for income, and the local government, which wants to get a grip on the spread of rubber farms without hurting the economic interests of the farmers or its own tax revenues.

“I just wanted to do something useful,” Yi said. For the Xishuangbanna government, which lacked important baseline data on its rubber industry, Yi’s work could be very useful.

After four years of research, Yi concluded that more than fifty percent of Xishuangbanna could be made off-limits to rubber plantations. It wouldn’t be very difficult to do so, she said, provided that the local government made a real effort to implement and enforce her plan.

Her solution:

- Conversion of land more than 3,000 feet above sea level or with a slope steeper than twenty-four degrees should be banned outright, as economical rubber production is typically impossible under such conditions.

- Rubber plantations located in strategic “biodiversity corridors” connecting the region’s increasingly fractured pockets of existing natural forest should be converted back into natural forest to facilitate the spread of flora and fauna.

- The government should provide private rubber farmers with the knowledge and skill set accumulated by state farms, which are twenty-five percent more productive per hectare than small private farms.

- Rubber farmers whose land must be converted back into natural forest, and those whose land is crossed by streams, should be compensated based upon income derived from international carbon and water markets where established benchmark prices could help establish appropriate compensation for converted land.

- For Xishuangbanna to keep its rubber industry without sacrificing its economic interests, the local government will need to get serious about monitoring plantations, enforcing land conversion bans, and grasping the intricacies of fairly paying farmers not to farm.

Easier said than done—and it seems the current window of opportunity will not be open for long. Should the Xishuangbanna government decide to act against runaway plantations soon—and it has not gone on the record to say that it will—positive results would be noticeable in just a few years, Yi said.

“In Xishuangbanna, it wouldn’t take too long— tropical forests are the easiest to regenerate. It’s really just a matter of there being a will to make it happen.”