Does Sina Weibo provide an equal platform for expression for both men and women in China? According to a recent study conducted by Sun Huan, a graduate student in Comparative Media Studies and a research assistant at the Center for Civic Media at MIT, the answer is probably no.

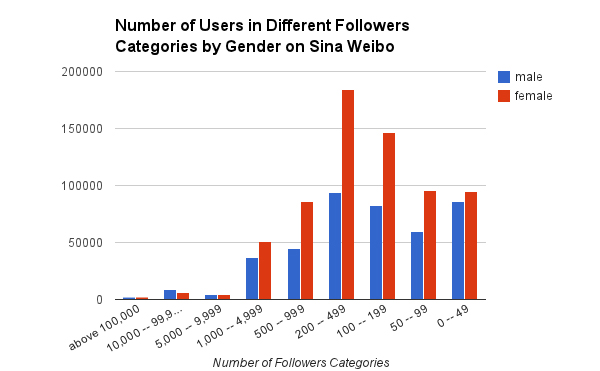

Through analysis of over 1 million Sina Weibo messages during Chunwan (春晚), a state-sponsored television program, to celebrate the Chinese New Year, Sun found that within the data, though over 60% of users are female, male users are almost twice as likely to have a large number of followers (5,000 or more) than their female counterparts, as shown in the graph below.

(Image copyright Sun Huan; reposted with permission)

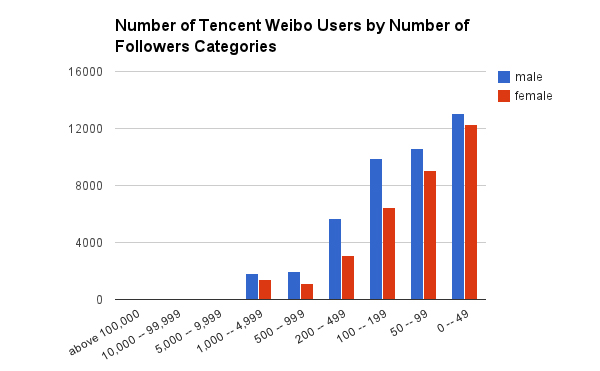

Similar results have been found from a sample of 76,730 users from Tencent Weibo, another micro-blog platform in China, which claimed to have over 100 million registered users in 2011. According to Sun’s study, both the number and followers of male users’ accounts exceed those of female users’ accounts—56.3% of the account users in the sample are male, while 43.7% are female. The graph below indicates that male users have more followers than female users do in each category.

(Image copyright Sun Huan; reposted with permission)

In a recent interview, Sun Huan shared more of her insights regarding the gender gap in the Chinese social media sphere with Tea Leaf Nation:

Are you a regular Weibo user yourself? If so, do your findings seem in line with your personal experience online?

I consider myself a regular Weibo user, and I often post or repost one or two messages per day. Even though sometimes I might not be posting, I log onto the site and see what others say on Weibo several times a day. I never really count how many of my friends on Weibo are female or male, but I definitely feel many people I follow who have tens of thousands of followers (so-called “da hao” or 大号) are male. … Many people I follow are in the field of journalism, technology, and nonprofits. My personal impression is that the leaders in these fields are mostly male.

What if anything does your study say more broadly about Chinese society or women in China?

There are several ways to evaluate the representativeness of my current dataset. First, we are not sure if the sample returned from Sina is representative of all the Weibo users who posted during Chunwan. Their API [or “application programming interface,” which allows more direct access to a website’s data] document only says it is not real time, and does not specify the sampling process. But the public timeline is the best we can get given my Chunwan research purposes. Second, we need to think about who are these Weibo users. Are they mostly urban? What is their age range? Which population groups are left out? Answers to these questions help us think about representativeness and give us some ideas answering your second question. My data shows the top three provincial-level locations with the most people posting during Chunwan were Guangdong, Beijing, and Shanghai. If we compare it with the population structure in these provinces, we probably can see that Weibo culture is very urban. I did a simple geographic distribution graph from my data set:

(Image copyright Sun Huan; reposted with permission)

I guess this Chunwan distribution is very aligned with the baseline Weibo user distribution as provincial-level places such as Guangdong, Shanghai, Beijing, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Fujian, and so on have large a number of users who posted during Chunwan. Even though we cannot make more generalizable claims given this dataset, the gender presence on Weibo at least is a lens for us to think about gender inequality in Chinese society. Some might argue that male users with a very large number of followers are very good at communication on Weibo. If we control this communication variable, what are some of other factors influencing their number of followers? What about their professions? Are males more likely to be in these better professions than females? I think answering this set of questions can help us see some aspects of social inequality in Chinese society through the lens of Weibo.

According to the distribution of male accounts on Weibo, it seems that there are more male accounts at the high end (with lots of followers) and a relatively smaller gender gap at the lower end. Is this interpretation correct? Does this distribution imply anything about which gender is more influential in shaping public opinions and their user behaviors?

I think your notion of a “gender gap” captures the essence of what I want to say in my graph. The calculation is not complicated: since we have the baseline, which is the average of the gender distribution of users across all number of followers categories, we compare the gender distribution of a specific category with this baseline. For your second question, I would be cautious about making such generalized claims. Public opinion shaping is quite a complex process in which Weibo is not the only player. Mainstream media is still very powerful in generating discourse and often it is hard to get data for gender presence in mainstream media.

Did you see any difference between the user populations of Chinese microblogging providers Sina and Tencent?

The Tencent data is a courtesy from Soshio (a Chinese social media analytics company). Their data shows more males than females on Tencent Weibo. So far we still do not know how to obtain the age variable from Weibo data.

* * *

The result is echoed by Sina Weibo’s official website. According to Sina Weibo’s Celebrity Influences Ranking, which is generated by a formula consisting of the level of activity, communication, and coverage, on March 19, among the fifty most influential Sina Weibo accounts, only fifteen were female (see circled accounts in image below). These accounts are of either singers, actresses, entertainment hosts, or writers on relationship and romance issues. Maybe it is still a long journey for females to be more influential on social media in China, as Global Voices editor Oiwan Lam said in a recent interview with the website Women’s Forum:

Ordinary women are not as active as men in expressing their ideas online, even though many of them have access to the internet. Most of the online public agenda are shaped by men. More and more women opinion leaders are emerging with the rise of social media and they have tried to engage with the public in a more dialogical way when compared to the male counterpart. Women should grasp the opportunities to shape the online public sphere and engage the public with gender and feminist perspectives by actively commenting on current affairs and social incidents.

(Rachel Wang/Tea Leaf Nation)