Ever since China’s new leader, Xi Jinping, first uttered the phrase “China Dream” last year, people in China and abroad have been scrambling to decipher its meaning. Many nations have “dreams”; in Canada, the country’s most prominent popular historian used the word to refer to building a trans-continental railroad in the nineteenth century to link the vast, sparsely populated country. But it’s probably best known in connection with the American Dream of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It seems unlikely that Xi meant to exalt individual freedoms in this way, especially because he uttered “China Dream” at an exhibition celebrating the Communist Party. In fact, a nationwide barrage of propaganda posters that went up starting in July gives a clearer explanation of what he is up to. Using the China Dream slogan, these posters extol various national virtues like filial piety and thrift.

I’ve seen these posters in several Chinese cities, such as Chengdu, Datong, and, of course, Beijing. Just down the street from where I live is a sports stadium, and out front are ten covered bulletin boards where Party newspapers are pinned up for people to read. In days past, these boards were important ways to spread propaganda; now they’re mostly frequented by older people, who peer intently at the articles. Next to the posted newspapers are spaces for advertisements, but for the past few months they’ve been covered with the China Dream posters.

Propaganda posters have a long tradition in Communist China, beginning with posters in the 1950s that celebrated the new revolution and urged support for the Korean War. (A selection of these were reprinted in a recent book, Chinese Propaganda Posters.) Xi Jinping’s China Dream posters are linked to this earlier era of Communist sloganeering. The difference is that while the old posters touted Communist values, the new ones largely replace them with pre-Communist Chinese traditions—drawing on traditional folk art like paper cutouts, woodblock prints, and clay figurines to illustrate their message. This is a redefinition of the state’s vision from a Marxist utopia to a Confucian, family-centric nation, defined by a quiet life of respecting the elderly and saving for the future.

The art is courtesy of well known folk art institutions, such as the Yangliuqing woodblock printing workshops outside of Tianjin, Henan’s Wuyang peasant paintings, and the paintings of the late Shanghai artist Feng Zikai—a sign of the Party’s ability to mobilize pretty much any social organization it wants, and to appropriate symbols that it once condemned. Almost all the art used in the posters, with its depictions of traditional dress and poses, used to be derided by the Party as belonging to China’s backward, pre-Communist past; now, these aesthetic traditions are a bulwark used to legitimize the Party as a guardian and creator of the country’s hopes and aspirations.

One of the chief promoters of the campaign has been a pro-government blogger named Xie Shaoqing, who goes by the nom de plume of Yi Qing. His writings—mostly homilies and Party slogans—grace many of the posters, and in his blog he describes how the posters went up this summer in Tiananmen Square. Based on his blog, Yi Qing would be categorized in China as a neo-leftist: there are entries attacking the investigative newspaper Southern Weekend, a paean to Chairman Mao on his birthday, as well as a guilt-ridden admission that he wrote the introduction to a book penned by the imprisoned police chief of Chongqing, Wang Lijun, whose former boss was the disgraced former Politburo member Bo Xilai. (Wang’s flight to the U.S. embassy precipitated the leadership crisis last year that resulted in Bo’s conviction for corruption and abuse of power; Bo is now appealing a life sentence.)

Yi Qing apologized for having written the introduction but then went on to praise Bo’s policies aimed at reviving traditional Communist culture. Choosing Yi Qing as the principal writer for the campaign is perhaps another sign that President Xi, while deeply suspicious of Bo’s ambitions, didn’t object to his old-style Communist values. Here is a selection of the China Dream posters, with some of the slogans translated and explained:

Ian Johnson

“The fatherland’s future of our country is springtime”—spring being the best time in the traditional Chinese calendar.

Ian Johnson

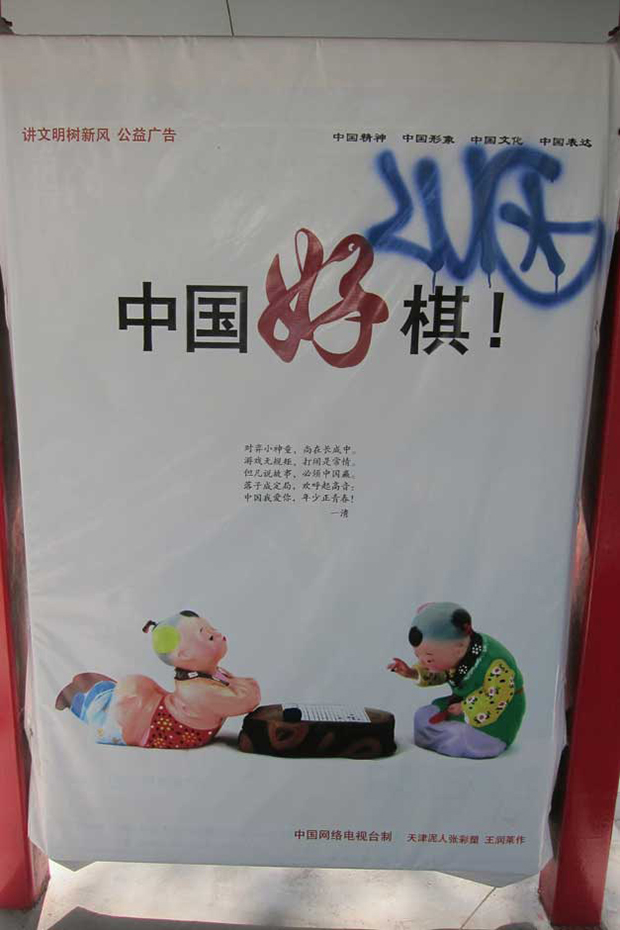

“My dream, China’s dream”: A young girl (a traditional clay figurine from the Tianjin workshop of Nirenzhang) sits pensively; below her a prose poem by Yi Qing describes a “dream-eyed” girl and ends with the lines “Ah China/My dream/A truly fragrant dream.” Interestingly, this particular poster, which I came across in Beijing, has been tagged by a graffiti artist—a rarity in China. It’s hard to know the vandal’s intention, but some of the spraying is accompanied by slashing, suggesting a political motive—perhaps it is meant to convey opposition to the growing leftist tendency in official propaganda.

Ian Johnson

“Young people are strong; China is strong”

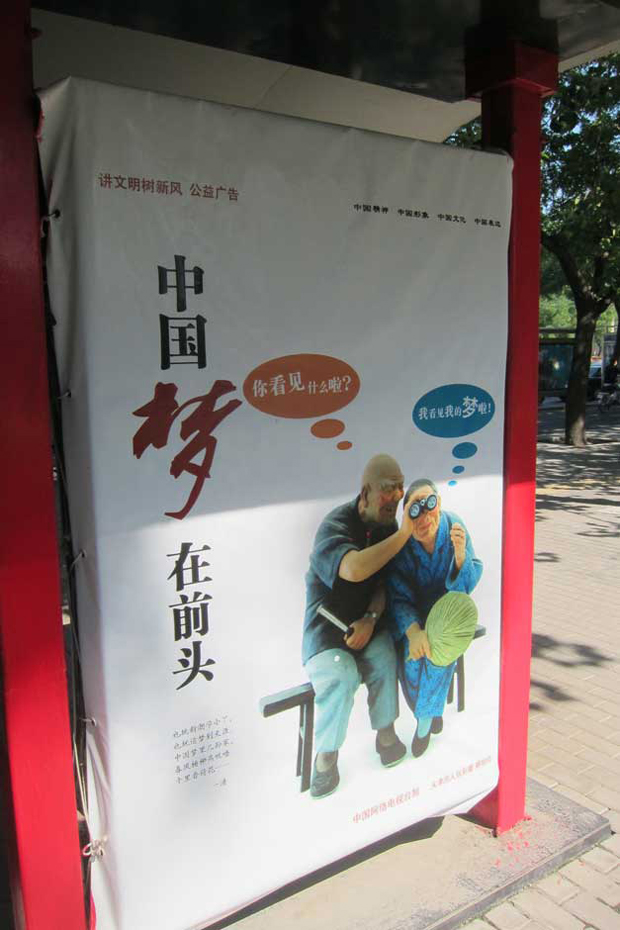

Ian Johnson

“The China Dream is ahead”: In speech balloons, the man says, “What do you see?” and the woman answers, “I see my dream!” This is one of the rare instances of humor in the series.

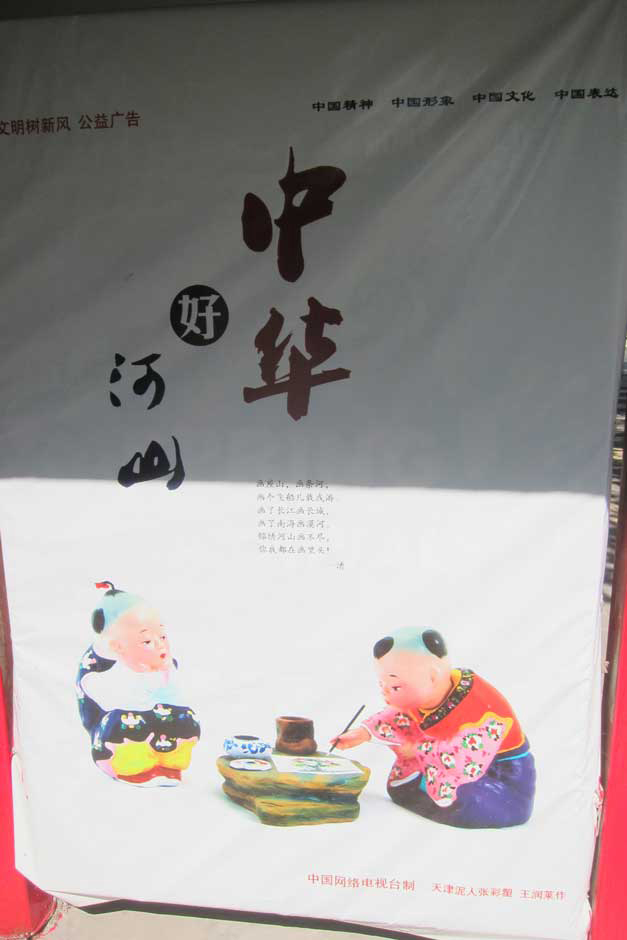

Ian Johnson

“China has good mountains and rivers”: in other words, the country is beautiful.

![“Big love [for] China”: The clay figurines depict military personnel helping at a natural disaster. The slashing is a rare attack on propaganda.](http://www.chinafile.us/images/4210/Johnson6.jpg)

Ian Johnson

“Big love [for] China”: The clay figurines depict military personnel helping at a natural disaster. The slashing is a rare attack on propaganda.

Ian Johnson

“Honesty and consideration handed down generation by generation; poems and books (or alternately The Book of Poems and The Book of History) last forever”: A traditional saying adapted to the campaign. Curiously, the little boy’s head has been cut out.

Ian Johnson

“Communists on the road to fulfilling the dream”: This is one of the explicitly pro-Communist slogans in the series. It’s accompanied by a poem by another writer, Shao Ling, that makes use of a series of Communist clichés: “Feet shackled, hands cuffed/sturdy grass withstands strong winds/the Communist Party members on the road/the mountains can shake, their will is unshakeable/hot blood and spring flowers will write today’s history.”

Ian Johnson

“Chinese boy and girls, serve the country”: This mild patriotic message is further softened by a peasant painting of children at play.

Ian Johnson

“A loud song for fulfilling the dream”: Xibaipo, the name appearing at the bottom of the poster, was the name of the headquarters of the Communist Party during the latter phases of the civil war. It has become a pilgrimage site for leaders like Xi, who recently visited it to extol the virtues of modesty and prudence.

Ian Johnson

“Good game China”: This is an odd poster, with the children playing a game of Chinese chess. The Chinese phrase hao qi, which I translated as “good game,” is used after someone has made a powerful move against someone else—something analogous to “checkmate.” The implication seems to be that China is winning, but against who is unclear—other countries? History? Fate? Or maybe one shouldn't read too much into propaganda campaigns masterminded by left-wing bloggers.