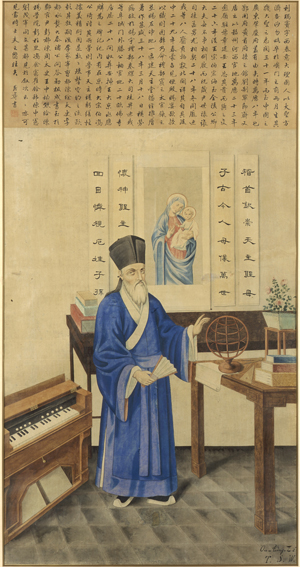

Courtesy of the USF Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History A portrait of Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci by You Wenhui; painted at the time of Ricci’s death in Beijing, 1610. It now hangs at the Jesuit residence in Rome. It is the only known depiction of Ricci taken “from life.”

When Matteo Ricci walked the streets of Beijing more than 400 years ago, he was a celebrity. The Jesuit was the first westerner to enter the gates of the Forbidden City. He impressed the emperor by predicting solar eclipses. He created an enormous map that gave Ming dynasty Chinese a sense of the rest of the world for the first time. He spoke and read Chinese well enough to translate Euclid.

And even though, after thirteen years in China, he began to dress in the garb of an imperial scholar-official, his goal was to convert Chinese to Catholicism, which he did with some success and considerable flair.

Now all he needs is a miracle or two. Literally.

In May, the Vatican body that overseas canonization pushed ahead the case for making Ricci, who died in 1610, a saint. The Catholic Church has collected hundreds of documents that provide evidence of his “heroic virtues” and has dubbed him a Servant of God, which puts him on the first rung of four steps toward full-fledged sainthood. In order for him to advance, Ricci’s supporters must now find evidence of popular devotion to Ricci, that prayers to him have cured fatal illnesses, or that his body hasn’t decayed in the 403 years since his death.

That next step might take some time, says the Reverend Gianni Criveller, a scholar at the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions in Hong Kong, who is assembling the historic documents for the process. Several years ago, Criveller says, a woman said she had been cured of an illness after praying to Ricci, but church officials didn’t think it was a strong-enough claim. The woman was sick, prayed to Ricci, and got well, but her case did not meet the qualification of a healing that was “complete, sudden, and cannot be explained according to medical knowledge,” Criveller says, “To make a long story short, the miracle is not there.”

Meanwhile, the real miracle might be something even more elusive: reconciliation between the Catholic Church and Beijing. Observers of Church-China relations say that the Vatican’s push to beatify Ricci now could be a political maneuver, a way to repair relations that have splintered.

Courtesy of the USF Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History The “Zikawei painting” of Ricci was one of four painted at the Jesuit orphanage of Xujiahui (“Zikawei” district of Shanghai) in 1914 for the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco.

Ricci has long been a symbol of how to get along with China. In a catechism called “The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven,” Ricci melded Chinese culture and Catholicism, arguing through a Socratic dialogue that Confucianism had in its beliefs the idea of a monotheistic being, shangdi. “A lot of myth-making rests on his shoulders,” says Liam Brockey, a historian of early modern Europe who is one of the foremost experts on the Jesuits’ attempts to convert China. Dominican and Franciscan missionaries felt Ricci had gone too far in drawing parallels between the two belief systems, and that controversy in part led to the Vatican’s later decision to reject the use of Chinese rites in Catholic services.

That’s what makes Matteo Ricci the “perfect image of what is a good relationship between China and the West,” says the Reverend Michel Marcil of the U.S. Catholic China Bureau in Berkeley, California.

Catholic-Chinese relations have had a rollercoaster history, with much of the ride stalled in the dips. Ricci’s tolerance of Chinese tradition included allowing new converts to continue to venerate their ancestors in religious practice. This tolerance continued for a century, until the Pope sent an emissary to Beijing to forbid missionaries from continuing the practice on pain of excommunication. The Kangxi emperor called the pope’s decree “petty” and insisted that all missionaries sign a certificate allowing Christian converts to continue practicing ancestor worship. Many of the Jesuits agreed; other Catholic missionaries refused and were expelled from China.

Rome reversed its decision against Chinese practices finally in 1939. After 1949, of course, the issue was moot. But another low point came in 2000, when Pope John Paul II canonized 120 Chinese martyrs, many of them killed during the Boxer Rebellion—and did it on October 1, the anniversary of the founding of the communist state.

Relations climbed back to a higher point in more recent years, as the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association—the Communist Party-run bureaucracy that oversees the sanctioned Church in China—and the Vatican agreed to appoint at least some bishops simultaneously. But in 2011, the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association, the P.R.C.’s official Catholic Church, reversed that trend and started inserting its own bishops into church positions.

In July 2012, Shanghai Bishop Thaddeus Ma Daqin suddenly resigned from the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association during his consecration. He received a standing ovation from members of the congregation after that announcement, but then was put under house arrest, where he remains today.

That, and the death in December of Shanghai’s ninety-seven-year-old Bishop Jin Luxian, makes a gesture towards rapprochement even less likely. Jin had wanted Ricci to be beatified along with one of Ricci’s contemporaries, named “Paul” Xu Guangqi. Xu, a scholar and colleague of Matteo Ricci, lived simultaneously as a Catholic and an imperial official, and translated several Western texts with Ricci. The thinking, says Thierry Meynard, International Director of the Beijing Center for Chinese Studies, a Jesuit research center, was that the Chinese would be more accepting of a dual beatification: one Westerner (and a good one at that) and one Chinese. But with the recent twists, the Vatican has put that process on hold.

In May, the newly anointed Pope Francis, a Jesuit, called upon the faithful to be more like Matteo Ricci and the Jesuits to build bridges and “establish a dialogue with all persons, even those who don’t share the Christian faith.”

It is a sure sign that something deliberate is happening. “I think the Vatican wants to make sure that if there is going to be a beatification, it’s going to help the Catholic Church in China,” says Meynard.

Whether that process is positive or not depends on your point of view, says Wang Meixiu, a scholar of world religions at Beijing’s Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Catholics think the move is positive, but “those outside of the church—they might think differently,” she says. While the Chinese people have great respect for Ricci, “at this sensitive period of time in history, to have him beatified is another thing.”

Brockey wonders who is behind the push for sainthood. “I don’t know whose interest it serves to have his beatification,” he says. But anyone who reviewed the historic record would see that “the man was not a saint, no two ways about it,” as Brockey says.

R. Po-Chia Hsia, author of A Jesuit in the Forbidden City and a Professor of History at Penn State, agrees. “If he’s canonized, I’ll have to eat my words,” he says. Historian Jonathan Spence’s The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci describes scenes of Ricci shouting down Buddhist monks at dinner parties. And Ricci went to plenty of dinner parties, writes Spence. He called the Chinese “barbarians” in letters home to friends and observed that slavery might be one of God’s ways to eventually convert people to Christianity.

Despite these shortcomings, beatification might be a fitting end for a man who defied expectations in life and in death. When Ricci died in 1610, Emperor Wanli ordered an imperial burial in Beijing, an honor no foreigner before him had been granted.

Today, his tomb rests in a cemetery lined with cypresses and pines in a quiet corner of Beijing. Ironically, the Jesuit’s eternal resting place—along with other Jesuit missionaries—is on the grounds of the Beijing Administrative College, the municipal training center for cadres of the Communist Party.

On March 13, the day that Francis, the first Jesuit Pope, was elected, a fresh bouquet of flowers mysteriously appeared on Ricci’s gravesite, says Phil Midland, a businessman who happened to be visiting that day. It seemed a fitting link between two groundbreakers.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Father Gianni Criveller as a Jesuit.